Town Manager Dave Bullock provides Siesta Key Association members details about the undertaking and about the island’s permeable adjustable groins

The Town of Longboat Key is paying close to $11 million for what is essentially “designer sand” being hauled in by truck from a mine in the vicinity of Immokalee in Collier County, Town Manager Dave Bullock told about 40 members of the Siesta Key Association (SKA) during their monthly meeting on May 5.

The expense is about twice what it would be if the town could use inlet sand, he pointed out.

Although the town also will be dredging the channels in New Pass and Longboat Pass this year, Bullock explained, neither those projects nor a source located in the Gulf of Mexico would yield the approximately 200,000 cubic yards of sand needed to renourish about 5 miles of Longboat’s beach. Therefore, town leaders chose to haul sand in by trucks that come off Interstate 75 and travel west on Fruitville Road, over the Ringling Bridge and the Coon Key Bridge, onto St. Armands and then to the property of the former Colony Resort, Bullock continued. There, the sand is dumped into piles before being loaded onto special types of vehicles that deliver it to the appropriate places along the beach, he said. Two hundred loads a day are arriving on the trucks, he added, and those trucks are spaced about five minutes apart.

“We’ve been doing it now for 35 days,” Bullock told the SKA members. “We’ve received two complaints.”

He spoke with Sarasota City Manager Tom Barwin that morning, he said, and Barwin reported only two complaints about the trucks.

The only snafu as of that point, Bullock noted, was an incident that happened about 6:30 a.m. one day: Too many of the trucks hauling the sand arrived at close to the same time, when the unloading site already was at maximum capacity. They ended up traveling down the turn lane on Gulf of Mexico Drive, he added. That taught town staff and the contractor the lesson that it was best to use an off-site staging area, Bullock continued. There the trucks can be queued up to wait their turns at the Colony, he told The Sarasota News Leader in a follow-up telephone interview on May 9.

“It is a highly coordinated effort, or you get these kinds of problems,” he explained to the SKA members.

Every truck is weighed, and it undergoes a Florida Department of Transportation inspection, he pointed out; the drivers carry slips with them that show the trucks’ weight. The vehicles are using only state roads, he noted. “The event is not so intensive or [the trucks] so heavy” as to produce immediate effects on the roads, he added.

“We needed sand bad, because Mother Nature has no respect for barrier islands,” he told the SKA members. Yet, the people who live in the condominium complexes and houses along the shore “want lots of beach.”

The Town of Longboat Key is not the only local government body to employ the truck-hauling method, he said. Broward County just completed a project that entailed 800,000 cubic yards of sand, he noted, and Collier County last year undertook a renourishment initiative that involved 250,000 cubic yards of sand.

Still, he explained, of the three possible sand sources for such a project, hauling it in by truck is the most expensive, based on the Town of Longboat Key’s experience. Using sand dredged from an inlet costs between $16 and $20 a cubic yard; sand in the Gulf of Mexico costs about $25 to $30 a cubic yard; and the cost of hauling it in by trucks ranges between $40 and $60 a cubic yard, he said. Right now, Longboat is paying $52 to $54 a cubic yard.

The cost comparisons have been readily available, he added, since the town is preparing to dredge the New Pass and Longboat Pass channels this year. Moreover, he told the SKA members, it is necessary to obtain permits for the dredging, regardless of the amount of sand involved. “And all pass permitting is difficult.”

It took the town two-and-a-half years to get the permit to dredge New Pass, he said; for Longboat Pass, three years. The expense involved has run from $300,000 to $500,00 just for the permitting, he pointed out.

Dredging offshore entails extra costs just in terms of getting the equipment in place to start the work, he noted. That can run from $3 million to $5 million. As for the sand that comes onto shore through a pipeline, he added, “The quality is whatever comes out.”

‘Designer sand’

“The best sand is inland in Florida,” Bullock explained. It comes from Immokalee and from the easternmost part of Lee County or Hendry County.

“We [specified] the color and spec’d the grain size,” he added, as well as the amount of organic matter in it and its moisture level. The grain size is important, he explained, because the finer the grain, the faster it erodes from the beach.

“It’s kind of designer sand. … It’s beautiful [but] it’s not Siesta Key sand.” Still, he continued, “It matches Longboat Key very well.”

The mine from which Longboat is getting its sand, he added, probably has millions and millions of cubic yards. He called it “a great vein of white sand.”

Furthermore, Bullock said, the permitting process is much easier.

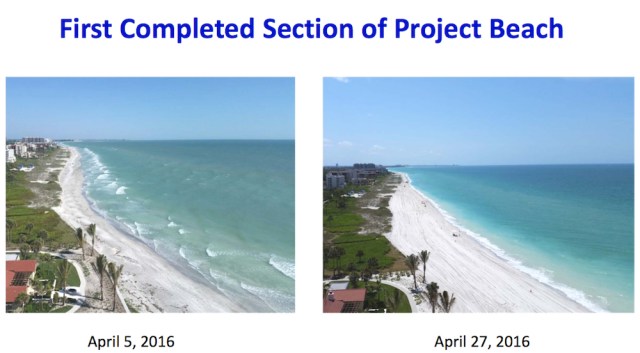

Bullock had gallon-size plastic bags with samples of sand taken from the beach before the renourishment began as well as the new sand. He told the News Leader in the follow-up telephone interview that he enjoys providing that type of comparison to audiences. “It’s whiter when we finish renourishing,” he said of the beach.

Each load of sand is sampled before the truck hauling it is allowed to dump it onto the staging area, he told the SKA members. And measures are in place to make certain, for example, that no driver has decided to set up a side business of selling sand, he pointed out.

The majority of the project’s expense, Bullock told the News Leader, is shouldered by the town’s property owners, on whom a tax is imposed that is “always approved by referendum.” The “cocktail of funding,” he said, also includes Tourist Development Tax revenue from both Sarasota and Manatee counties that is set aside each year for the town. Additionally, Bullock continued, “we have been reasonably successful in getting a series of state grants” through the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the Legislature to cover part of the cost.

Permeable adjustable groins

Along with his discussion about the renourishment project, Bullock provided the SKA members information about the permeable adjustable groins (PAGs) on Longboat Key.

The four concrete structures stretch out about 200 feet into the Gulf of Mexico, Bullock said. “For many, many years,” he continued, nothing the town tried seemed to stop the erosion on the beach. Then, in 2010, it constructed the first two groins, though “it took a long time” to win the necessary state permit to put them in place.

They are built on pilings that go down about 25 feet into the Gulf, he noted, and they are “very storm-resistant.”

Each groin has a multitude of 100-pound blocks in it; they are held in place by steel pins. The design was planned for the structures to slow down the flow of water in the Gulf so more sediment drops out, he continued, “and it works.”

After they had been in place for a while, Bullock said, it became clear that the section of beach just south of them was being starved of sand, “so we had to loosen ’em up.” That entailed divers removing some of the blocks.

The town built the second two structures about a year ago, he added.

SKA Second Vice President Catherine Luckner and her husband, Bob — an engineer who serves on the organization’s Environmental Committee — have asked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers [USACE] why it has not considered using PAGs as part of its proposed $19 million project to renourish Lido Key. Planning for the joint effort of the USACE and the City of Sarasota includes two regular groins on South Lido. That project is still in the permitting stage at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

The USACE has not responded to the Luckners’ query.